Analysis: Why does the industry run on kinships?

The debate around the ugly head of nepotism continues to rear itself time and again in Bollywood. The past month has witnessed an escalation again due to the sudden death of actor Sushant Singh Rajput by suicide. Sushant is termed an "outsider" aka someone who finds success in an industry like Bollywood which is often dominated by "star kids". The trolling and online speculations over how or why the actor died has drowned out the core issues - which seems to have become a common path for social media led outrage.

Black & White photo of late actor Sushant Singh Rajput | May he rest in peace

As someone who has spent more than three years studying Bollywood for a PhD research, in this article I will outline the key elements that make the industry so heavily dependent on kinships, social networks and the entrenched dominance of a few film families. The aim here is to highlight the historical factors that have given Bollywood its shape, content and form.

Beware reader, this is going to be a slightly longer read than usual. So if you want to go into a deep dive with me into Bollywood, you’re welcome aboard.

First Act: The Flashback

Indian film production at the beginning was mostly carried out by individuals and entrepreneurs who invested their own capital and assets. It was the establishment of the film studio Bombay Talkies in 1934 that gave way to the film industry transitioning into a studio model. In the early 1940s, Mumbai, Kolkata and Chennai were thriving film industry centres with studios.

When India gained independence in 1947, Mumbai rose as a financial capital. As the prominent Indian port city, Mumbai not only witnessed an influx of migrants and emergence of a new class of businessmen or the nouveau riche, but also money and capital. This money had to be invested somewhere and films were a lucrative opportunity. Observing that there was already a crop of film stars that were popular, the investors started offering the stars separate film deals away from the studios. The stars on realising they could earn more money became independent from the studios. This eventually gave rise to the star system as we know it today.

Film Director Karan Johar is often referred to as the inventor of Nepotism

Let’s bring in more elements here; the business of film is inherently unpredictable and a high risk venture. An economist will tell you that the money invested in the production of a film is considered as a sunk cost; a necessary expenditure that cannot be recovered. To earn a profit, the producer has to earn more than the breakeven point. But a film is unlike a factory made product wherein one movie is the same as another. Demand is uncertain and sometimes films click and sometimes they don’t. Now, if as a producer I want to ensure the maximum returns possible, the safest outlet is to put my money in a renowned actor or director; betting my investment on a big star would ensure an audience footfall.

Let me highlight another interesting fact - up until the year 1998, the film industry in India was part of the informal or unorganised sector.

Now let THAT sink in. For a country that produces the world’s largest number of films annually, it was only in 1998 that the Indian government officially recognised the film industry. When an industry is part of the informal sector, it falls outside of the purview of government guidelines and monitoring. The income is not taxed and sources of finances are patchy or fragmented. Employment in the informal sector is characterised by insecure contracts, lack of worker benefits, representation and protection.

Second Act: 1998-Birth of an ‘Industry’

And so, for an individual and independent filmmaker to take a loan from a bank to make a film before 1998 was impossible.

If you’re a millennial reading this, remember Dawood and the underworld making news in early 1990s in the context of Bollywood. Post 1998, the biggest change for the film industry has been making its finances transparent and the ability for filmmakers to take bank loans.

The deeply entrenched system of ‘nepotism’ and the supremacy of film families exists due to the industry’s need to hedge its bet against uncertainty and get the maximum return on investment. The system for long has acted as a safety net and bulwark for the film industry.

Now let me drop another very surprising fact, a fact that has been reported in the latest FICCI-KPMG Media and Entertainment Report; the total number of film exhibition screens in India is 9,600 (China has close to 70,000 screens!). Annually, India produces close to 2000 films, factoring in the 52/53 weeks in a calendar year and Friday film releases, you can do the math on how many films get to be seen on the big screen! Even then, most screens are concentrated in metropolitan Indian cities.

Add to that, according to Statista’s Indian film industry’s box office data, even a cursory glance over the last decade reveals that close to 50% of the box office revenues come from Bollywood films, followed by Hollywood and then regional films.

Is it any surprise then that for an exhibitor the decision on which film to screen is motivated mostly by profit and star power rather than the content and aesthetical value of a film? And might I add, we too as audiences have been key enablers in perpetuating the star system and nepotism.

The Third Act: Netflix and Chill?

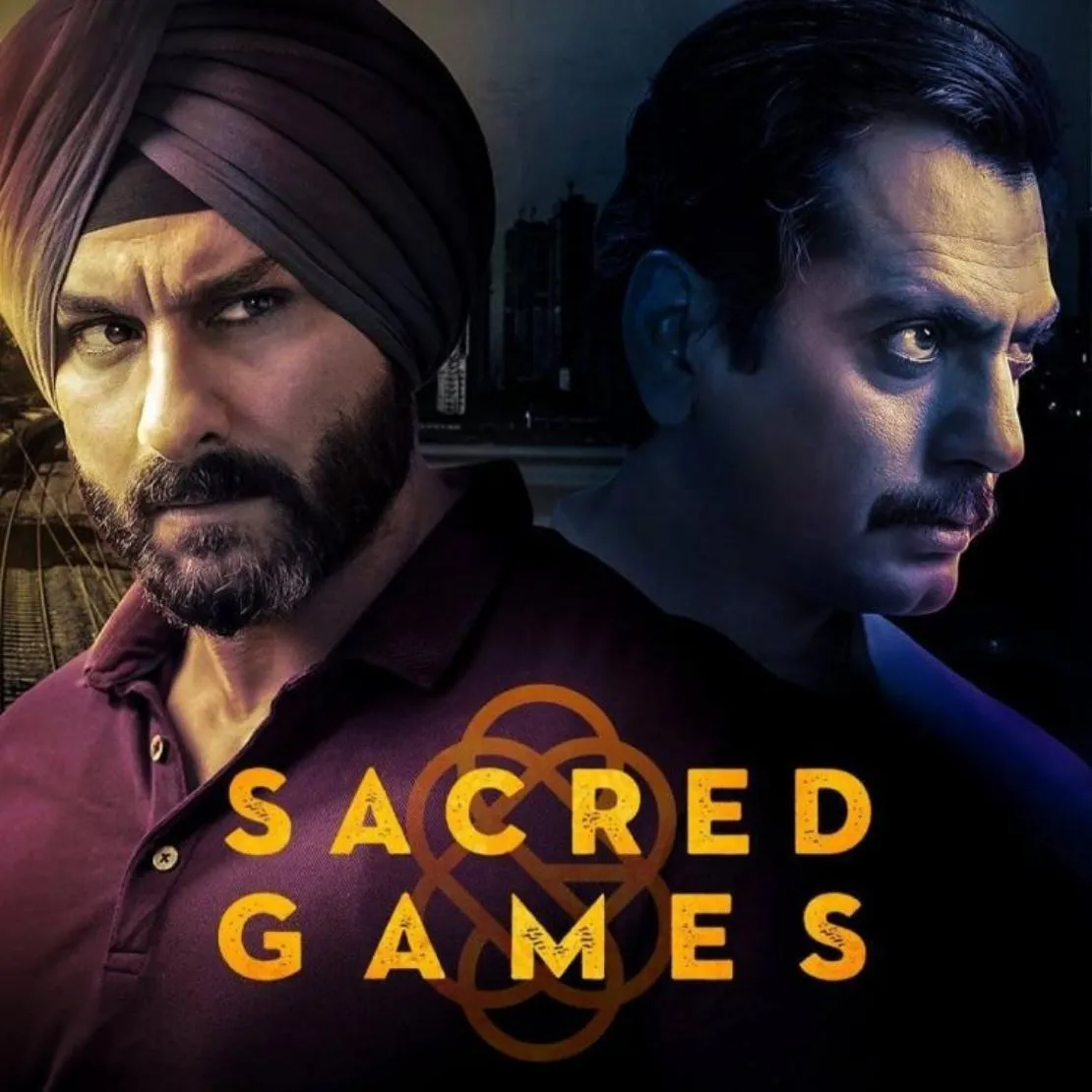

But the rise of Over The Top (OTT) platforms like Netflix, Amazon, Hotstar and Zee5 are turning out to be major game changers. Due to the abysmally low screen penetration in India, both domestic and international OTT platforms are in an enviable position of plugging into the huge gap in reaching out to the audience. India also has the world’s cheapest mobile data, an opportunity that online content distributors have been quick to capitalise on. They are disrupting decades old distribution and exhibition channels and the change has been further precipitated by the COVID pandemic.

Netflix India's first ever original series, Sacred Games

The recent film releases directly on the platforms instead of a theatrical release has had many in the industry debating the next transformations in horizon for Bollywood. The platforms are not only reshaping distribution, but also modifying the very nature and form of visual storytelling. International OTT players have given the audience access to high-value premium and daring content. Domestic OTT platforms have the advantage of producing hyperlocal content for regional audiences. With so much access to quality content, it is little wonder that audiences have recently been lashing out at films starring children of known faces with no story to vouch for.

So when the news about the death of actor Sushant Singh Rajput’s came to light, a major portion of the discussion was driven by collective years of dissatisfaction and anger.

Coming to the denouement or climax, as with any business and new innovations, the networks in place in Bollywood need to be rehauled to reduce barriers to entry and make way for more storytellers and actors from underrepresented communities in terms of caste and socio-economic class. Several mainstream actors and actresses acknowledge the presence of nepotism, but what’s more important is if anything tangible is being undertaken to make the industry more inclusive?

Will Karan Johar in addition to producing a Student of the Year (SOTY) for star children also produce one just for newcomers?

And importantly, as audiences of popular cinema, instead of just complaining and rising in vitriolic debates only after an actor’s death, can we actually rise to the occasion and support independent filmmakers and their work and demand a better industry?